Transmigration Reboot

Having been raised in a hippy/Buddhist/Sufi household, it’s not difficult to trace some of my philosophical origins. When I was 5 years old, my parents brought me to India as they pursued their musical and spiritual interests. Half the trip was spent in the Tibetan exiled community of Darmsala, where my parents and I were fortunate to have a private audience with His Holiness the Dali Lama. Upon returning to the states our home became a makeshift Buddhist center, hosting high Lamas and Rinpoches visiting San Francisco.

One of the great gifts of Buddhism, and other eastern religious philosophies, is the idea of reincarnation. As a child the simple idea of returning was both fascinating and comforting. The idea that one’s life is perpetual/cyclical, rather than singular and finite, resolves, or at least simplifies, one of life’s great mysteries. Not that mysteries are bad, but the idea that one’s existence becomes irrelevant, or even worse becomes trapped in eternal hell, can torment and even handicap those who dwell there. Throw in some original sin and you have a recipe for psychological imprisonment with no chance of postmortem bail.

As I’ve grown older and thought more deeply about life, death, religion, faith, atheism, psychology, and anything else that can shape my world view, I’ve been able to reconcile and refine my philosophy of life. In particular my personal understanding of life, death and the afterlife/pre-life have become increasingly clear. I can’t claim credit for the ideas, but the collection of ideas feel like my own, I think in part because they stand up to the rigors of my cynical, analytical side that has no tolerance for suspending disbelief. Also in part because they feel like universal truths.

The first idea I struggled with was the idea of reincarnation in a literal sense. It was intuitively difficult for me to believe one could exit their body, then return with any prior connection in tact. As I learned more about the Tibetan Buddhist system I developed my own side narrative, one where the experience is a result of collective will and faith more than transcendent reality. The great leap of faith happens once a Tulku dies and the Regent searches for the next Tulku, which appears to me an act of faith, projection and intuition. Once the Tulku is discovered, a specific form of re-education is used to restore the essence of the prior Tulku, creating a sense of continuity. Think about it, if you had the luxury of spending half your life teaching people everything you know, believe, feel, etc., then have those people train from a young age all those teaching, you have in essence continued the life and teachings of the prior life. It’s neither a scam nor illusion - it’s a reincarnation of the mind. The Dali Lama really does have the collective wisdom of the past 17 incarnations, but I personally believe it’s not at all because of transcendent capacity.

Now that we’ve tossed the comfort philosophy out the window, how do we return to everlasting self preservation? One of my first post-Buddhist philosophy-of-death reads was Guy Muchie’s The Seven Mysteries of Life, an ambitious book attempting to touch on a wide swath of reality. In his book he describes life as floating down a stream, where each bend of the river presents a new, previously unseen view. And death being an experience that brings the life-view up and above the river so one can see its entire form. Something about this analogy resonated with me and helped form the beginning of a new post-death philosophy.

I’m not sure where or when the next analogy surfaced, but I’ve since found the basic premise in many spiritual and philosophical contexts. The idea is simple. Life and all of reality is a giant flowing river and along the way are an endless series of waterfalls. At each waterfall countless droplets emerge and become momentarily isolated, then return to the river below. This momentary isolation is the life we experience as individuals. When we die we return to the life force of reality until we hit the next waterfall down river.

A story by Suzuki Roshi captures this idea beautifully.

I went to Yosemite National Park, and I saw some huge waterfalls. The highest one there is 1,340 feet high, and from it the water comes down like a curtain thrown from the top of the mountain. It does not seem to come down swiftly, as you might expect; it seems to come down very slowly because of the distance. And the water does not come down as one stream, but is separated into many tiny streams. From a distance it looks like a curtain. And I thought it must be a very difficult experience for each drop of water to come down from the top of such a high mountain. It takes time, you know, a long time, for the water finally to reach the bottom of the waterfall. And it seems to me that our human life may be like this. We have many difficult experiences in our life. But at the same time, I thought, the water was not originally separated, but was one whole river. Only when it is separated does it have some difficulty in falling. It is as if the water does not have any feeling of being separate when it is one whole river. Only when divided into many drops can it begin to have or express some separate feeling. Before we were born we had no such feeling; we were one with the universe. This is called ‘mind-only,’ or ‘essence of mind,’ or ‘big mind.’ After we are separated by birth from this oneness, as the water falling from the waterfall is separated by the wind and rocks, then we have such feelings. And you have difficulty because of such feelings. You attach to the feeling you have without knowing just how this kind of feeling is created. When you do not realize that you are one with the river, or one with the universe, you have fear. Whether it is separated into drops or not, water is water. Our life and death are the same thing. When we realize this fact, we have no fear of death anymore and we have no actual difficulty in our life.

- Shunryu Suzuki Roshi

The last part of this puzzle, and one that inspired me to write this, comes back to consciousness, or the sense that we are individual, unique and special beings. This seems to be the aspect of leaving one’s body that is the most difficult to accept - the idea that the experience of oneself will be no more. While I personally feel consciousness is just a veil at the end of ones life, it will likely continue to be THE essential mystery.

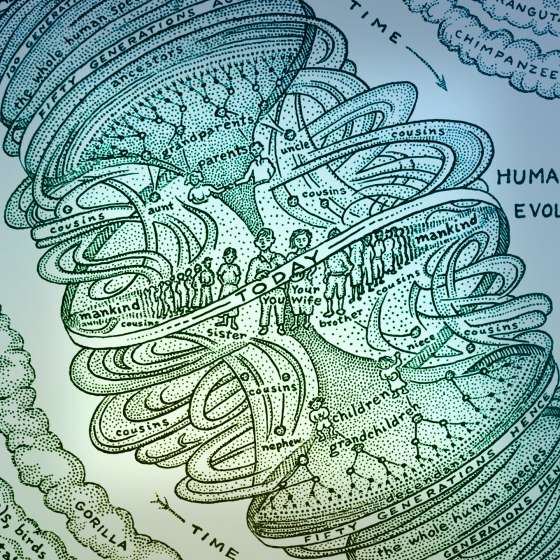

What has become more clear is a sense that the essence of our conscious selves continues to grow and expand long after we leave our bodies. Our collective influence provides the guidance for a sort of meta-ego. In essence, we continue to reincarnate through procreation and our DNA. Giving birth and raising a child has the same potential of the reincarnation of high lamas, only factors such as attention, culture, tradition, and other variables obscure a direct transference of consciousness. But the impact of a deeply rooted genetic foundation, combined with learning and influence, is the continuation and accumulation of our entire lineage of life.

While I can’t say my philosophy is as carefree and simple as it once was, but I’m returning to a place of ease and confidence that life is unfolding as it should and post-life is only the beginning… or maybe the middle. Certainly not the end.

Posted

Aug 13, 2010