Hunting Mushrooms

Likely before I uttered my first coherent words I was crawling around in the dirt looking for gourmet edible mushrooms. A story my aunt likes to share, which I have absolutely no memory, is when I found the “biggie” — a Boletus Edulis nearly the size of my three-year-old torso. My father is a passionate mushroom nerd — a mycologist is what the academics call them. He’s a walking encyclopedia of mushroom names and characteristics, nearly always knowing the Latin names, common names, identification characteristics, and edibility.

Boletes are upwards of 50 pounds and can stand at two feet tall. They are the inspiration for giant toad stool mushrooms in fairy tales. They’re also delicious — a rich, steak-like flavor that can stand on its own as a meal or enhance an egg breakfast or pasta dinner.

My father comes from a family of mushroom hunters. Mushroom nerds call foraging for mushrooms "mushroom hunting" because it’s often hard to find the good ones, and potentially fatal to find the bad ones. Finding them often requires wandering off-trail and heading deep into the woods, looking for traces or evidence of their presence, and often return home empty-handed — foiled by the elusive creatures. Just because they don’t move doesn’t make them less tricky to track and find. My father claims he can "hear" the vibration of certain mushroom species — with my understanding that mycelium (vegetative part of a fungus) permeates the ground below our feet, I don't doubt his claim, although I've never "heard" them myself.

I now understand that mushrooms are complex organisms with particular habitat needs. There seems to be a direct correlation between how tasty a mushroom is and their habitat fastidiousness. For example, boletes likes thick ground cover from pine trees, where they can grow a foot tall before breaking through the surface. Boletes also like a perfect mix of dryness and moisture, so they often grow in coastal areas where fog gives them steady moisture, and like the south-west side of a hill or large tree where the ground dries out a bit. The chanterelle prefers older oak trees, where a deep mulch has had time to develop, and likes the cooler north-east facing side of a hill. Morels often propagate under pine trees, and just below the melting snow line in the Sierra foothills in the springtime.

Another factor in finding mushrooms is the fierce competition. Gourmet mushrooms are a favorite food of wild pigs/boars, and with their keen sense of smell and low visual perspective, they usually find them long before they push through the forest floor (duff). Deer and other forest animals also love mushrooms. If the animals don’t get them, a small army of professional foragers often clean up in the more accessible areas. The most sought after mushrooms (Chanterelles, Boletus, Morels, Truffles) have all evaded commercialized cultivation at scale — a testament to the mysterious and complex nature of fruiting fungus.

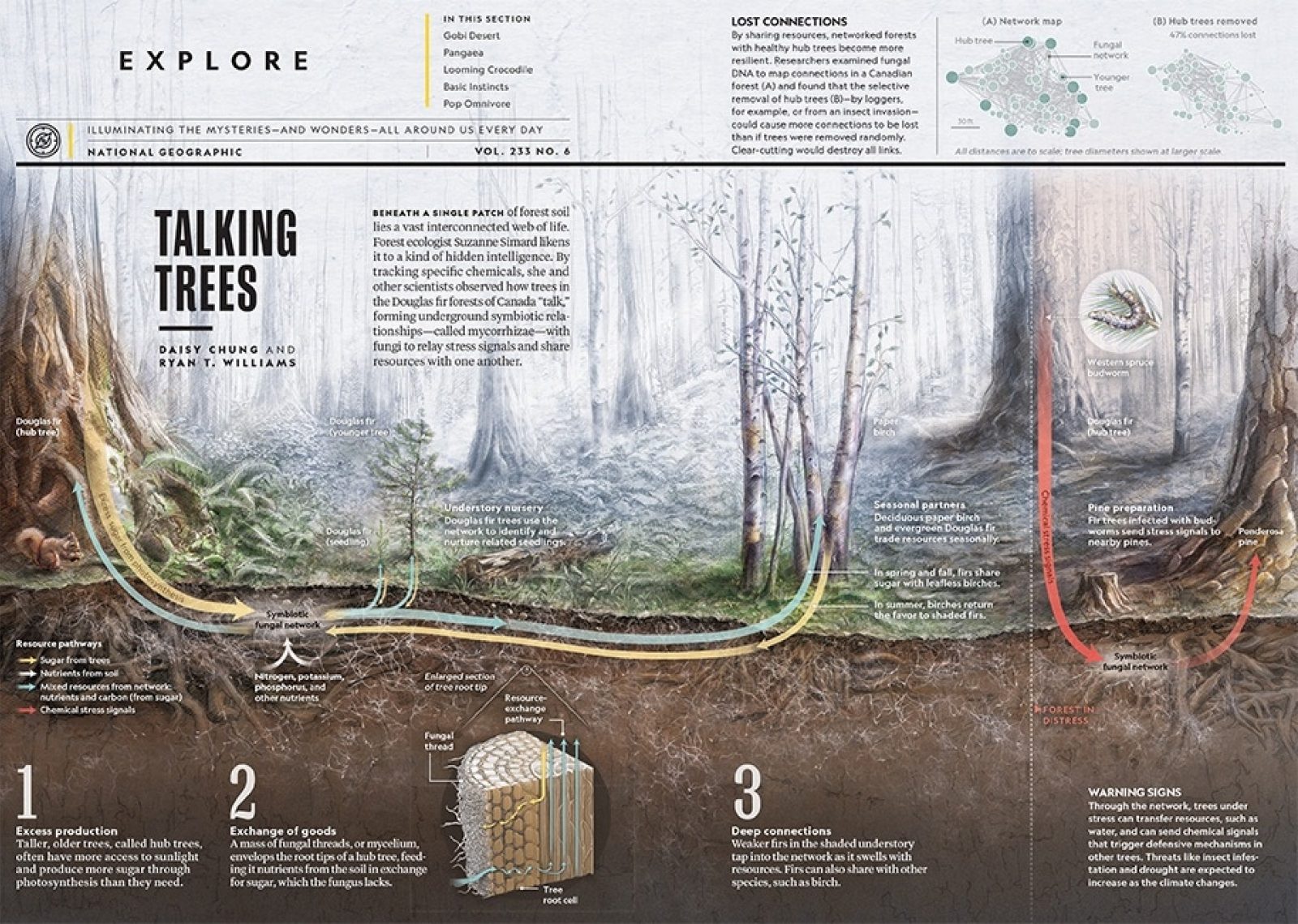

I recently read the book "The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from A Secret World" by Peter Wohlleben, which goes into great detail about how fungus facilitates communication between trees and are a required ingredient in the health of a forest. Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, is the largest organism on the planet — potentially stretching for miles underground. The mushrooms we see are just fruiting body of the mycelium. The mycelium becomes intertwined with tree roots, and from Wohlleben's book and recent studies, we now know that mycelium is both a conduit for food and a communication medium for the trees. The trees can literally talk to each other through the fungus network. One critical communication they enable is early warnings about disease and invasive insects — giving neighboring trees a formula for defense. Trees, in return, give the mycelium salt and water. Fascinating!

My interest in mushrooms has been cultivated from a young age, and I’m trying to do the same for my two daughters. Since they were old enough to walk I’ve been bringing them to look for mushrooms. We have random mushroom chachkies throughout the house — mushroom pillows, salt shakers, t-shirts. I’m not obsessed — I only keep the good stuff 😉

So, this story isn’t only about the mushrooms in the woods. It’s also about the mushrooms in my mind — when you have a strong association with an object or idea, you see it wherever you go. My mind is clearly attuned to mushrooms and reminds me of my father telling me he could spot a mushroom in the woods out of the corner of his eye while driving 50 miles per hour — it wasn’t a visual identification exactly — more of an awareness.

In my early 20s I was excited about new music coming out of England called Acid Jazz. The name invoked both psychedelia and musical sophistication — two qualities I enjoy in music. My father being an incredible jazz musician, I grew up listening to some of the jazz greats and would go see people like Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter play live. I was also listening to a lot of House Music so Acid Jazz hit a sweet spot for me — jazz, funk, soul, electronic, dance — all mixed together. And by having the word “acid” in the name, people naturally put psychedelic references, including mushrooms, on album artwork and other promotional material.

In 1990, I started making mix tapes of my favorite Acid Jazz music. Some of the tapes were new music and some were mixes of music from the 60s and 70s that inspired Acid Jazz. I called my mix tapes “Mushroom Jazz” — it just made sense. Most of the tapes were one-offs for my own listening pleasure or a special gift for friend. I believe it was my 3rd or 4th tape that I gave to a friend of mine Eric who, along with my friend Charlie, worked at Anarchic, a notorious streetwear clothing company of the time.

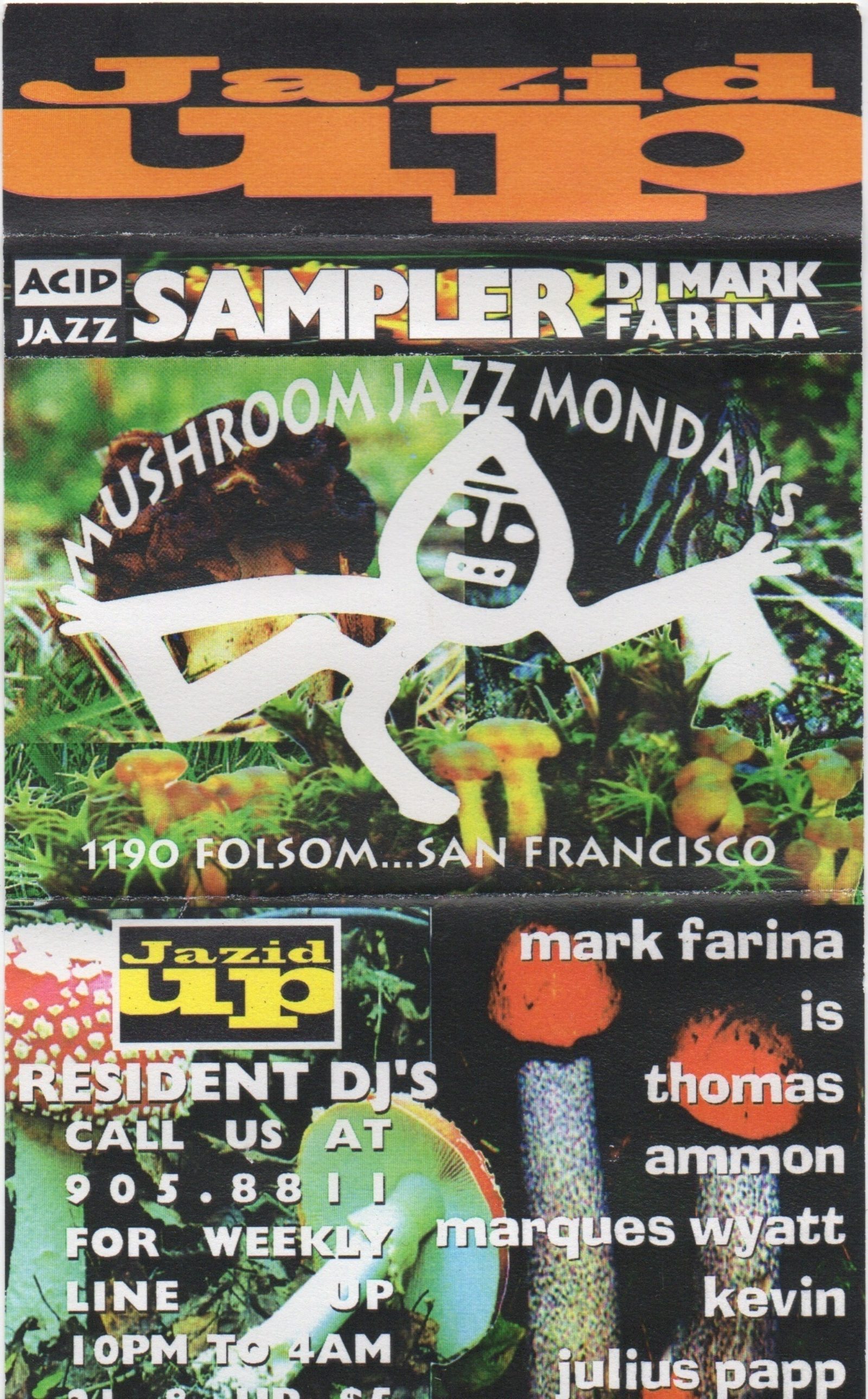

Eric and Charlie went on a trip to Chicago some time in late 91 or early 92 for a clothing trade show. They ended up staying with Mark Farina and Patty Smith — there was a music connection in there somewhere. Eric brought my tape and shared it with Mark and Patty. Mark was also fascinated with the growing Acid Jazz movement and was making his own mix tapes which, by coincidence, were also called Mushroom Jazz. Eric returned with Mark's tape and shared the serendipitous connection, which happened to be the best mix of Acid Jazz I had ever heard.

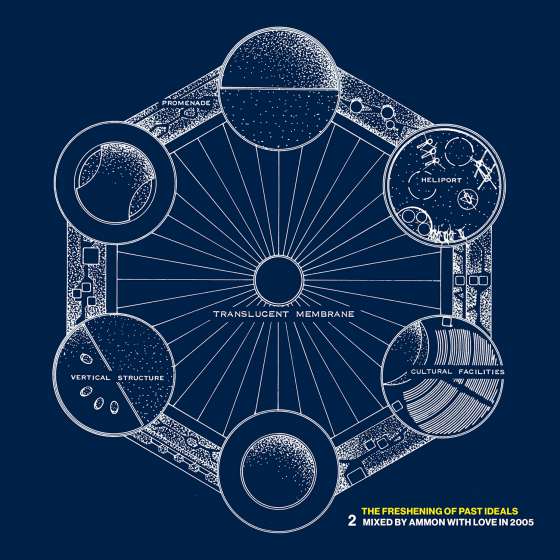

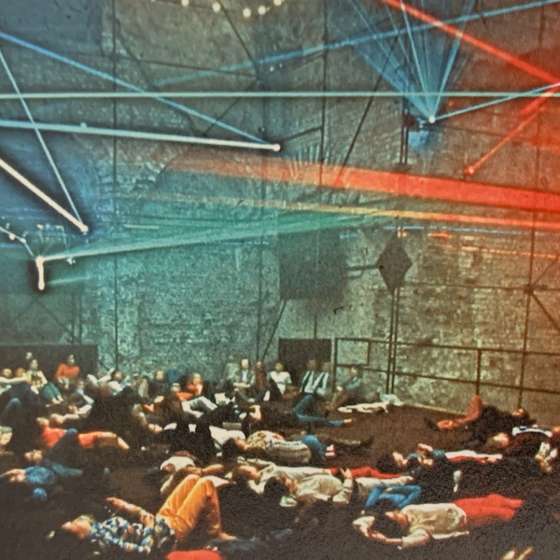

I was working at a tech startup called Colorscape, a CDRom development shop. My boss, Eric Kalabacos, was a fellow music lover and shared my passion for the music and culture that was flourishing in San Francisco. We were talking about creating a party where we could share music like Acid Jazz and downtempo — at the time all the parties were purely house or techno. He offered to bankroll the effort. At the same time Mark and Patty moved from Chicago to San Francisco and were looking for new opportunities — Mark was a full time DJ and Patty was an event promoter. We teamed up with the other Eric and formed a plan for our inaugural event.

In the summer of 1992 we held our first event, dubbed Jazzid Up!, at the Oasis nightclub in SF's SOMA. We had the idea of a space with great music, delicious food, socializing and dancing. Patty convinced us we should have the party weekly to build a following, and within a few weeks we were seeing a fairly full house. The event continued to grow in both size and reputation. We began attracting DJs and artists outside our community, such as DJ Shadow, Marques Wyatt, and bands such as the RAD and Slide Five.

While the official name of our weekly was Jazzid Up!, most people referred to the event as Mushroom Jazz, and there were plenty of mushrooms present on promotional materials and decorations. Mark continued to use the moniker as he became a globally recognized DJ and musician.

I’ll wrap up this meandering mushroom journey with a short film titled “Looking for Mushrøøms" by Brucə Connər (creative mis-spelling to delay the removal of the video). He shot the film while Connər was living in Mexico in the early 1960s. The film chronicles Connər, Timothy Leary and other friends as they attempt to find the psychedelic variety of mushrooms in rural Mexico. Set to my favorite Terry Riley track “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band”, the film is a meditation on the act of getting lost.

Posted

Mar 20, 2019